Village by Shannon: the story of Castleconnell and its hinterland was written by Joe Carroll and Pat Tuohy and published in 1991. In Chapter 7, “The Great Houses and Landmarks of Castleconnell”, they describe the area known as World’s End, in Castleconnell, Co Limerick. They say

World’s End, is a derivation from its original name, Worrall’s Inn […].

The story of Mr Worrall

According to Carroll and Tuohy, Joseph Worrall was from Yorkshire and had been an officer in the British Army for many years. He came to Ireland with the Cheshire regiment and was stationed in Offaly. When he retired from the army, in “the early years of the eighteenth century”, “he was given the riverside holding at Castleconnell” where “he erected a good size inn” and built a stone quay. At some unspecified later date, a dam was built three quarters of the way across the river to keep up the water levels. Worrall’s Inn became a busy trading post but lost business to the Limerick Navigation when it was opened in 1802. At some unspecified date Mr Worrall left his inn and returned to England.

I know nothing of Mr Worrall and such cursory searches as I have undertaken on the interweb have been fruitless, save that Wikipedia says that the Cheshire Regiment was indeed in Ireland from 1689 to 1702, with a short break in 1695. It does not appear to have returned to Ireland until 1970. It may not, however, have been known as the Cheshire Regiment, having “been called after its successive colonels” until 1751. However, there is nothing there that is inconsistent with Mr Worrall’s having served with the regiment in Ireland and retired therefrom in the early years of the eighteenth century.

But there are some aspects of the account in Village by Shannon that puzzle me because they do not accord with my understanding of the history of the Shannon navigation and the traffic thereon. The book does not cite any sources for the story of Mr Worrall and his inn and I am thus unable to attempt to resolve the differences between the book’s account and the evidence with which I am familiar.

The eighteenth-century Shannon

Village by Shannon says that “In that time” [presumably “the early years of the eighteenth century” when Mr Worrall arrived] the Shannon was “only navigable down as far as Castleconnell”. Accordingly, goods for Limerick, and other points further downstream, were unloaded there; goods from Limerick, destined for places upriver, were shipped from the quay. As a result, Mr Worrall’s inn attracted the custom of the “boatmen, merchants and other river travellers”; the landlord’s ale produced revelry, songs and occasional brawls.

The problem with this account is that, in the early eighteenth century, the Shannon was not navigable at Killaloe, except perhaps by small cots when conditions were right. Sean Kierse quotes some accounts by early visitors to the town:

The Shannon runs by the town [of Killaloe], and in this place is so rocky it is not navigable, so that all goods must be carried from Limerick till above the town by land, and being embarked there the river is again navigable for many miles. [John Stevens 1690]

The fall of the water here (at Killaloe) is very considerable, and in a distance of about fifty feet it falls fourteen or fifteen feet through large round stones. [De La Tocnaye 1797][1]

And Hely Dutton wrote in 1808

Until lately the navigation of the Shannon was incomplete, but by the exertions of the Board of Inland Navigation, aided most ably by Mr Brownrigg, the difficulties at Killaloe have been overcome, and now the communication not only from Dublin to Limerick, a distance of upwards of ninety miles, is completed, but also to the sea, which is sixty miles more.[2]

Three locks (one a double) were required to enable boats to get through Killaloe; the combined fall through the locks was 21′ 3½” (6.49 m). I cannot say when each of the locks was opened, but work on the Limerick Navigation, linking Limerick to Killaloe, did not begin until 1757. Thus in “the early years of the eighteenth century” cargo-carrying boats visiting Castleconnell from upriver could not have come from anywhere north of Killaloe, and it seems unlikely that there was sufficient traffic between there and Castleconnell to require the services of many “boatmen, merchants and other river travellers”.

It was not until the end of the eighteenth century that the navigation was completed, with the first boats travelling between Killaloe and Limerick in 1799; the first boat to reach Dublin from Limerick got there in 1806.[3] At that time there were only ten boats, of 15–20 tons, using the navigation,[4] none of them large enough to qualify as “river ships”. It therefore seems highly unlikely that there could have been any significant traffic, or any considerable number of thirsty boatmen, visiting Castleconnell in the early nineteenth century.

The Limerick Navigation

In a sense, Carroll and Tuohy agree, because they say that Mr Worrall was active a century earlier, that the “waterway between Limerick and O’Brien’s Bridge” was completed in 1802 and that it “spelt the end for Worrall’s trading-post as ships could now proceed all the way to Limerick city”.

But this suggests a misunderstanding of the nature of the Limerick Navigation. It was in five sections:

- a mile of canal from the harbour in Limerick to the Shannon

- a mile of river navigation up to Plassey, where the navigation crossed the river

- the Plassey–Errina Canal from there to Errina, between Castleconnell and O’Briensbridge

- another section of river navigation from there, upstream through O’Briensbridge to Cussane lock, at the lower end of the Killaloe canal. Access by water to Castleconnell from Limerick was on this section of river, by turning right (downstream) on leaving the Plassey–Errina Canal instead of going left (upstream) to Killaloe

- finally, a section of canal, with three locks, leading through Killaloe to Lough Derg.

The first four sections constitute the “waterway between Limerick and O’Brien’s Bridge”. But it was only the completion of the Limerick Navigation, and specifically of its final section, the Killaloe canal, that made Castleconnell accessible by water to “ships” or other vessels from Lough Derg, from anywhere upstream of Lough Derg along the Shannon or from Dublin by the Grand and Royal Canals. Until the Limerick Navigation was completed, Castleconnell was inaccessible by river from upstream as well as from down.

FOR BANAGHER, PORTUMNA, KILLALOE, O’BRIEN’S-BRIDGE, CASTLE CONNEL, AND LIMERICK

The Munster Lass, of Killaloe, John M’Keogh, Master, being the first vessel that ever came from Killaloe to Dublin, will take in loading at the Canal Harbour, James’s-street, for any of the above-mentioned towns, and returns to Limerick immediately. As the master is also owner, the shippers may rely upon the same unimpeached integrity and care that have ever distinguished the Killaloe boatmen.

Inquire of the Master on board, or at Mr Dowling’s Office, Canal Harbour, James’s-street.

The Master’s character will be vouched by Mr Brownrigg, Engineer, at No 34, Charlemont-street.

May 1st, 1804 20[5]

The early nineteenth century: the quay and the weir

Carroll and Tuohy say that Mr Worrall built a stone quay, where ships could berth, at his riverside holding at Castleconnell; they say that, at some unspecified later time, a dam was built, three quarters of the way across the river, to keep up the water level during the summer. They give no dates for the construction of either the quay or the dam (weir).

That might suggest that the structures currently at World’s End were built by Mr Worrall, but they were not. Mr Worrall may well have built a quay and a dam in the early eighteenth century but, if he did, they had disappeared by the 1830s. Thomas Rhodes mentioned no traces of any earlier quay or dam:

In the alterations at Castle Connell, I propose taking off a portion of the point upon the south side, as also a small bend upon the north side of the river; this portion to be reduced from the upper surface to the level of summer water, with several eel weirs to be cleared away, &c. The formation of a weir or dam at this place, similar to the one at Killaloe, would be the most effectual method. This site is very suitable for the erection of several powerful corn mills, having a good fall of water; and the part of the river above the fall being in nearly a tranquil state, vessels might be navigated close to the weir, bringing and taking away the produce, as may be required, from the mill by the canal. By reducing the head or surplus of water from Castle Connell to Cussane, it would save from inundation a considerable tract of land and bog on both sides of the river, which might be brought into a state of the highest cultivation.[6]

In 1837, the commissioners planning the improvement of the Shannon explained that a weir at World’s End would regulate the level of the water in summer, keeping 6 feet 6 inches on the upper sill of Errina Lock.[7] Their plans were implemented in the 1840s; the quay and weir currently at World’s End, Castleconnell, were built by the Shannon Commissioners between 1840 and 1843. They spent £981/18/1½ in 1840 [£163/19/3½ on works, £817/18/10 in payment of awards],[8] £2/5/3 in 1841,[9] £3052/11/1½ in 1842[10] and £1368/1/2 in 1843.[11]

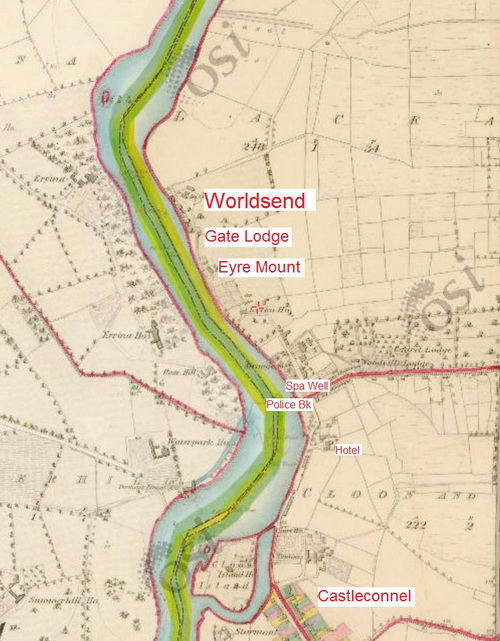

The 6″ Ordnance Survey map, completed before 1842, showing neither quay nor weir at Worldsend (OSI 6″ ~1840)

From the Commissioners’ report for 1842:

World’s End

The operations at this place were the clearing away a shoal which backed up the water in time of floods, and also the cutting away part of the left bank of the river, in order to obtain a greater discharge.

The length of the shoal which has been removed was 1250 feet, with an average breadth of 200 feet, and 4 feet deep; this space was enclosed by earthen dams of 680 lineal yards, and then unwatered by pumps. The work was commenced at the end of last June, and completed, with the exception of the removal of the dams, by the middle of November. About 9500 cubic yards of excavation, composed of sand, and a very hard description of limestone rock, were removed monthly.

To give the village of Castleconnell and the surrounding districts the benefit of the navigation of the Shannon, we took advantage of the stone turned out of the excavation to form a landing-quay, to which there is every facility for making a good road. The completion of the landing-quay and removal of the dams are the only works remaining to complete this contract.

The spirited manner in which Messrs Sykes and Brookfield, the contractors, have carried on their operations, both here and at Kildysart and Querrin on the Lower Shannon, is highly creditable to them.

The average number of persons employed daily at World’s End, from the 27th of June to the 25th December, was 270, being equivalent to 42182 days’ work.[12]

And from their report for 1843:

World’s End

As soon as the water in the river had fallen sufficiently low to permit of operations being resumed, the building of the quay wall was recommenced, and the work completed by the end of October 1843.

A regulating weir was formed across the river to keep up the water in summer to a proper level for the nevigation, and the dams removed. An excellent approach has been formed to the quay from Castle Connell. The inhabitants of this interesting village can now benefit by the navigation of the river, which previously could only be obtained after a considerable distance of land-carriage to O’Brien’s Bridge.

The average number of men employed daily at World’s End, from the 27th March to 8th October, was 23, being equivalent to 4223 days’ work.[13]

Note that there is no suggestion in either report that there had already been a quay or a weir or dam at World’s End; the road to the quay was new and the report for 1843 suggests that Castleconnell would, for the first time, be able to use the navigation.

Of course the fact that the current quay and weir did not exist before the 1840s does not prove that Mr Worrall, or someone else, did not erect a quay and a weir in the early 1700s. But if such a quay and weir did exist they seem to have fallen out of use (leaving no traces) before the current quay and weir were built. Thus there was — at the very least —a discontinuity in the use of the World’s End area by boats on the Shannon. The account by Carroll and Tuohy does not make that clear.

Nineteenth century passenger traffic

Carroll and Tuohy say that the completion of the Limerick Navigation deprived the Worrall’s Inn trading post of its raison d’être but that a “passenger service was introduced when a complete and unbroken waterway was opened up between Limerick and the Grand Canal to Dublin”. They say that the passenger boats were called paddle steamers and that the trip to Dublin often took a week.

This account is not entirely accurate. First, the waterway was not “complete and unbroken”, in ownership, management or transport services, although it was possible to purchase through tickets between Limerick and Dublin.

Between 1800 and 1850, the Limerick Navigation, from Limerick to Killaloe, was controlled in succession by the Limerick Navigation Company, the Directors General of Inland Navigation, the [new] Limerick Navigation Company, the Shannon Commissioners and the Board of Works.[14] Lough Derg, from Killlaloe to Portumna, was open to all boats, with neither controls nor tolls, but the Directors General of Inland Navigation had some buoys erected. The Directors were succeeded by the Shannon Commissioners and then the Board of Works.[15] The Shannon between Portumna and Athlone — the “Middle Shannon” — was transferred by the Directors General to the Grand Canal Company but compulsorily purchased from them by the Shannon Commissioners, who then passed it on to the Board of Works.[16] Finally, the Grand Canal was the property of, and controlled and operated by, the Grand Canal Company — or Company of the Undertakers of the Grand Canal, as it was known up to 1848.[17]

Starting from Limerick, a traveller would be carried on a mile of canal, a mile of river, a longer canal, another river stretch, a short canal at Killaloe, a lake, a river and, finally, a long canal to Dublin. On the first five of those, ie on the Limerick Navigation, the traveller would probably have been in a horse-drawn passage-boat, operated by a contractor, although from 1827 there were occasional experiments with the use of small steamers.

At Killaloe, the traveller would have transferred to a paddle steamer: before steamers came into use on Lough Derg, there was no regular, frequent passenger service on the Shannon. The first steamer service was operated by John Grantham between 1827 and 1829, when his boats were taken over by the Inland Steam Navigation Company; in 1833, its operations were subsumed by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company.

The steamer would have taken the traveller to Portumna where, until the Derry shoal was dredged in the 1840s, passengers transferred to a smaller steamer, which took them up the river to Shannon Harbour. (Once the shoal had been dredged, larger steamers were able to travel the whole way.) At Shannon Harbour, passengers took the Grand Canal Company’s horse-drawn passage-boat to Dublin. Thus the traveller would have used at least three, and possibly four, boats between Limerick and Dublin.

But despite all the changes of vessel the journey did not take anything like a week:

Passengers leaving Portobello [in Dublin], by the Grand Canal Boat, at Two o’Clock in the Afternoon of every day, except Saturday, will reach Limerick or Ennis the following afternoon — and Passengers leaving Limerick at Six o’Clock, or Ennis at Five o’Clock, in the Morning of every day, except Sunday, will arrive at Dublin the following Morning.

REDUCED FARES BETWEEN LIMERICK AND DUBLIN

First Cabin 13s 6d

Second Cabin 9s 6dFARES BETWEEN DUBLIN AND ENNIS

First Cabin 16s 6d

Second Cabin 12s 6dLuggage free to First Cabin 84 lbs

Second Cabin 42 lbs[18]

Passenger traffic to and from Castleconnell

Carroll and Tuohy say that hundreds of people, emigrating from the area in the 1820s and 1830s, left from Worrall’s Inn and that “Scenes of tearful farewells at the little harbour were commonplace”. They add that, in the late 1840s, Worrall’s Inn witnessed “an even greater tragedy in the exodus of people fleeing from the Great Hunger”.

The 6″ Ordnance Survey map — all surveying was completed by 1841 — does not show any inn at World’s End; it does show a house called Worldsend. It does not show any harbour or quay; Thomas Rhodes’s evidence shows that neither quay nor weir existed in the early nineteenth century. And, if Mr Worrall set up his inn in the early eighteenth century, he would have been long dead by the early nineteenth century.

The passenger-carrying boats may not have existed either. I am not aware of any evidence that there was ever a passenger service to Castleconnell, and I would be surprised if there was such a service. First, a horse-drawn passage-boat from Castleconnell would have had to go upriver to O’Briensbridge to cross the Shannon, before going downstream on the County Clare bank to the entrance to the Plassey–Errina Canal. It is conceivable that ropes, buoys, winches or ferry-boats might have been used to allow a crossing directly to the upper end of the canal, as they were at the lower end at Plassey, but I know of no evidence for their existence.

Second, there was no towing-path or trackway, and (as far as I know) no easement permitting passage along the banks, between Castleconnell and O’Briensbridge, or even between Castleconnell and a point opposite the upper end of the canal.

Third, the journey by water from Castleconnell to Limerick would have been much longer, in distance and time, than that by road; I can see no reason why anyone would go by boat rather than (depending on their means) by carriage, by car or on foot.

Steam-powered passage-boats could have overcome the first two problems: they needed no trackways and could have crossed the river wherever they wanted to. However, steamers were rarely used and I have found no evidence that they ever visited Castleconnell.

Indeed I have found no evidence that any passenger-carrying vessel ever used the quay at the World’s End in Castleconnell. The 2nd–11th reports of the Commissioners for Improving the Navigation of the Shannon give the numbers of passengers embarking on the boats of the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company during each month from January 1840 to December 1849; Castleconnell is not listed as a place of embarkation.

Penal transportation

Carroll and Tuohy say that, from the turn of the [presumably nineteenth] century, the “little quayside” [which did not then exist] featured in a “trade in human misery”, “beginning with the dreadful years of transportation of convicts to New South Wales”. They say that convicts were kept under lock and key, and chained together, at Eyre Mount, later known as the Old Barrack, then brought to Worrall’s Inn, “then the nearest point of departure”, whence 141 of them travelled, in some unspecified period, on one of three named steamers “down the canal on the first leg of their journey to join the larger ships at Limerick Docks for the long voyage to Australia”.

I do not know whether Eyre Mount was ever a place of confinement for convicts or whether it was ever known as the “Old Barrack”. The 6″ Ordnance Survey map shows a Police Barrack near the Spa Well, not at Eyre Mount. But, that apart, there are two significant problems with this account.

Of the three steamers named, I have no information about the Minerva, which is not listed by Ruth Delany[19], by D B McNeill[20] or by Andrew Bowcock.[21] The other two, the Lady Betty Balfour and the Countess Cadogan, were built in Paisley in 1897 and employed on the Shannon, by the Shannon Development Company, until 1913. However, penal transportation ended in 1868.

The second problem is that, as far as I can see, no convict ship left from Limerick for the Australian colonies, at least from 1826 onwards, ie during the steam age on the non-tidal Shannon. The Convicts to Australia website draws on Charles Bateson’s work[22] to list all the convict ships reaching the Australian colonies. All vessels from Ireland that went to Norfolk Island, Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia, in or after 1826, left from either Dublin or Cork. The same is true of all but two of the vessels from Ireland to New South Wales. For the two exceptions, no port is specified: the place of departure is given as “Ireland”. However, the first of them, the Florentia in 1830, carried 200 convicts, none of whom had been convicted in Ireland. And the second, the Hive in 1835, sailed from the Cove of Cork on 24 August 1835.[23]

Carroll and Tuohy describe convicts being taken by steamer from World’s End, Castleconnell, to Limerick to be transported to the Australian penal settlements; I cannot see how that accords with the evidence.

Summing up

The central claim made by Carroll and Tuohy is that the area of Castleconnell known as World’s End derived its name from Worrall’s Inn, and that Mr Worrall was a former army officer who operated his inn in the early eighteenth century. I have nothing to say about that: I know nothing of Mr Worrall and I don’t know what sources provided Carroll and Tuohy with their information.

Carroll and Tuohy claim that Worrall’s Inn was a trading post and that merchants and boat crews provided Mr Worrall with significant business. The claim seems to be to be at odds with what we know of the navigation of the Shannon in eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and it would therefore be nice to know what evidence Carroll and Tuohy used. It may be that their evidence would cause a revision of the history of the Shannon navigation.

Carroll and Tuohy say that Worrall built a quay and a dam. If he did, there was no trace of them by the 1830s. Again, it would be nice to know what evidence Carroll and Tuohy used.

Carroll and Tuohy say that passenger-carrying boats served Castleconnell. I know of no evidence to that effect and I would very much like to know what their evidence is.

Carroll and Tuohy say that convicts were carried by steamer from Castleconnell to Limerick, where they were transferred to convict ships and taken to Australia. That seems to be at odds with what we know about passenger services on the Limerick Navigation and about transportation to Australia.

In short, Carroll and Tuohy make several claims that do not accord with what is known about the history of the Shannon and its navigation. It would therefore be extremely useful to know what evidence they used, as their contentions might require some rewriting of the Shannon’s history.

Envoi

Incidentally, the Ordnance Survey Name Books do not agree with Carroll and Tuohy about the source of the name “World’s End”. The entry for World’s End (Lacka) [PDF], by JO’D, says

World’s end

Situated in the W side of Lacka townland and within 1 chains of the river Shannon.

It has taken its name as world’s end in consequence of the road ending there at the edge of the bog, then but now reclaimed.

Sources

[1] Sean Kierse The Killaloe Anthology Boru Books 2001

[2] Hely Dutton Statistical survey of the county of Clare, with observations of the means of improvement; drawn up for the consideration, and by direction of the Dublin Society 1808

[3] Saunders’s News-Letter, and Daily Advertiser 11 October 1806

[4] Charlotte Murphy “The Limerick Navigation Company 1697–1929” in North Munster Antiquarian Journal Vol XXII 1980

[5] Saunders’s News-Letter, and Daily Advertiser 2 & 3 May 1804

[6] “No 10. Second Report upon the Means of Improving the Shannon Navigation, and of Reducing the Waters of Lough Derg from the Winter or Flooded State, to the Ordinary Summer Level. Thomas Rhodes” in River Shannon Navigation. Copies of a Letter from the Chief Secretary of Ireland, respecting the River Shannon, and of Answers to the Same Ordered, by The House of Commons, to be Printed, 11 August 1832 [731]

[7] Second Report of the Commissioners appointed pursuant to the Act 5 & 6 William IV Cap 67 for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon; with Maps, Plans and Estimates Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. HMSO, Dublin 1837

[8] Second Report of the Commissioners for Improving the Navigation of the Shannon; with an Appendix Ordered, by The House of Commons, to be Printed, 26 February 1841 [88]

[9] The Third Report of the Commissioners for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon, Ireland; with an Appendix Ordered, by The House of Commons to be Printed, 2 March 1842 [71]

[10] Fourth Annual Report of the Commissioners for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon, Ireland; with an Appendix Ordered, by The House of Commons, to be Printed, 6 March 1843 [76]

[11] Fifth Annual Report of the Commissioners for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon, Ireland; with an Appendix Ordered, by The House fo Commons, to be Printed 26 March 1844 [151]

[12] Fourth Annual Report of the Commissioners for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon, Ireland; with an Appendix Ordered, by The House fo Commons, to be Printed 6 March 1843 [76]

[13] Fifth Annual Report of the Commissioners for the Improvement of the Navigation of the River Shannon, Ireland; with an Appendix Ordered, by The House fo Commons, to be Printed 26 March 1844 [151]

[14] Ruth Delany The Shannon Navigation Lilliput Press, Dublin 2008

[15] ibid

[16] ibid

[17] Ruth Delany The Grand Canal of Ireland David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1973

[18] Dublin Evening Mail 16 May 1838

[19] Ruth Delany The Shannon Navigation op cit

[20] D B McNeill Irish Passenger Steamship Services Volume 2: South of Ireland David & Charles, Newton Abbot 1971. There was a Minerva, wrecked in 1854, based in Cork; it was never on the Shannon

[21] Andrew Bowcock “Early iron ships on the River Shannon” The Mariner’s Mirror Vol 92 No 3 August 2006

[22] Charles Bateson The convict ships 1787–1868 2nd ed 1974 is cited; I take that to be the Australian edition

[23] Southern Reporter and Cork Commercial Courier 27 August 1835

[lknav37]

Great site. Have enjoyed reading and referencing it over the years. What an interesting mystery! The World’s End seems to pop up a lot in searches alright, and it smacks of that period in history when sailing boats plied their trade, and as new parts of the world were ‘discovered’, they were added to the map (usually by the colonisers), and great tales were brought back to home port. No doubt the World’s End pub in London (there are several, in fact) was replete with great stories from sailors in its day. Every year, ‘we’ discovered a new end of the world, it seems.

It seems like an odd story to invent (Retired army man Worrall builds inn and quay, etc.) if there is very little of any historical or archaeological evidence to back it up. Is there any possibility that he did indeed have some form of landing site in order to get goods onto the Shannon for downstream transport mainly? Given the site may have been close to a main road? It would have been the first place to do so, after Killaloe. Clutching at straws maybe. But for a brief period, it may have made sense? I’m thinking, for example, of Lyons Village on the Grand near Sallins, which boomed and then vanished.

No doubt maps such as Taylor and Skinner would show us when the original World’s End house appears, but it does seem to roughly tally with the story.

I’m curious ‘coz my wife and I just signed up to the triathlon there, and we were a wee bit curious (nervous) why it was so named ;-)

Thanks again for a great resource.

Pingback: The Mystery of World’s End – unironedman

You can’t navigate downstream from the World’s End (unless in a kayak, which doesn’t carry many tons of cargo). You can’t do it now and you couldn’t do it at any time: the Falls of Doonass make it impossible.

The quay at World’s End, and the road to it from the village, were built by the Shannon Commissioners in the 1840s.

Upstream, you could (and can) go to O’Briensbridge, but (given that there is a convenient road, once the mail-coach road to Dublin) I can’t see why you would want to. You couldn’t get through Killaloe until the Limerick Navigation was completed.

As far as I’m concerned, it is possible that there was a Mr Worrall and that he had an inn; however, I cannot see how he could have made a living from serving drink to non-existent sailors.

bjg

A good answer. And as for my part, better to remain silent and be thought a fool, as they say. Thanks for the reply. Mr Worrall remains a mystery for now.

Any evidence of Turf Boats using the pier ?

Fascinating article as I visit Worlds End very regularly. I always believed that Worlds end was derived from Worral’s end as given in the foregoing article. Perhaps with the ending of the trade post it assumed the nomenclature Worral’s end .

Either way I don’t think we will ever know. Nonetheless thanks to everyone who researched all the narratives.